Because in Japan, it’s not what you say—it’s how gently you say it. It’s not just showing up—it’s showing you care.

Japan is a land of breathtaking contrasts. One moment, you’re standing beneath the neon lights of Shibuya, and the next, you’re quietly bowing at a centuries-old shrine. But beyond the beauty, the discipline, and the quiet magic lies something many foreigners miss: the nuances—the unspoken rules, the subtle gestures, the quiet ways of saying, “I see you. I respect you. I belong.”

When I first came to Japan, everything looked like a beautiful dream—clean streets, quiet trains, people bowing and smiling with grace. But behind that serene beauty, I felt something I couldn’t quite explain… like there was a language I hadn’t yet learned. Not Japanese words—but gestures, silences, and rhythms of life that didn’t need to be spoken, yet meant everything.

As a foreigner, I often felt unsure. Was I being too direct? Did I speak too loudly on the train? Why did people hesitate before saying “no”? These small moments started to whisper something to me: there is a deeper layer to life in Japan. One that no textbook ever really prepares you for. One that’s made of nuances.

Japanese nuances aren’t just cultural habits. They are quiet forms of respect. They’re the reasons people apologize even when they’re not at fault, why gifts are wrapped so thoughtfully, and why listening can sometimes be more powerful than speaking. They’re the invisible threads that hold society together—delicate, respectful, often unspoken, but incredibly powerful. These cultural intricacies show up in the way people speak, how they behave at work, how they raise their children, how they walk through life with deep awareness of the people around them.

And I realized… if I truly wanted to live here—not just exist here—I had to understand this invisible world.

As foreigners—whether you’ve come to visit, work, study, or raise a family here—understanding these nuances is more than a survival skill. It’s a bridge. It allows us to truly connect, not just coexist. It helps us earn quiet respect, build authentic relationships, and avoid unintentional missteps that could create distance or discomfort.

So why should you learn them? Because…

- When you know how to read the air (kuuki o yomu), you begin to truly understand your Japanese coworkers or neighbors—even when they say nothing at all.

- When you realize why silence on the train matters, you stop seeing it as coldness and start seeing it as kindness.

- When you bow not just with your head but with your heart, people feel it.

These nuances aren’t rules meant to restrict you—they’re gifts meant to guide you. They help you live, work, and love in Japan with more grace, empathy, and ease.

In this blog, we’ll gently open the curtain and reveal the deeply human truths behind Japanese social cues, workplace customs, language expressions, parenting philosophies, and more. Not to judge or compare, but to understand—and grow. Each section is rooted in real experiences, cultural insight, and a deep respect for both the Japanese perspective and the foreigner’s journey.

Because once you understand the nuances… you no longer feel like a stranger. You feel like you belong.

1. Workplace Nuances: Working in Japan Isn’t Just About the Job — It’s About the Group

Japan’s workplace culture is founded on harmony (和, wa), respect for hierarchy, and a strong sense of group responsibility. It’s not just about what you accomplish individually—but how well you support the collective, show humility, and quietly contribute to the team’s balance.

When you start working in here, you quickly realize that the real work happens not just at your desk—but in how you connect with your team. As a foreigner, understanding these subtleties can mean the difference between standing out for the wrong reasons… or being quietly respected for how well you fit in.

Senpai-Kōhai: The Unspoken Hierarchy

This isn’t just a senior-junior thing—it’s a cultural structure rooted deeply in how Japanese people build trust. A senpai is expected to guide, protect, and mentor, while the kōhai shows humility, asks for advice, and never oversteps.

For example: If you’re new in a company, don’t feel shy about asking your more experienced colleague for advice. It actually honors the system and makes them feel respected.

What to do: If you receive advice, thank them warmly. If you succeed, credit your senpai. Observe who defers to whom. Use honorific language with superiors. Offer tea or documents with both hands. Your awareness shows respect more than words ever could. These small actions reflect emotional intelligence that will gain quiet admiration.

Wa: Putting Group Harmony First

In many Asian and Western workplaces, sharing bold ideas is celebrated. In Japan, harmony comes first. Even if someone disagrees with you, they might say something like, “That’s interesting—maybe we can think about another way?” They’re trying not to disrupt the group’s flow.

What to do: Practice listening more than talking. Observe how others express disagreement subtly. You’ll begin to sense when “yes” actually means “no,” and when silence says more than words ever could.

Indirect Communication: The Art of Reading the Air (Kuuki o Yomu)

Literally meaning “to read the air,” this Japanese expression refers to sensing the mood of the room and adjusting your behavior or words accordingly.

Example:

If everyone is working quietly and you loudly share a joke, you might be told to “read the air.” If someone is tired or uncomfortable, others will avoid burdening them without needing to say a word.

How to apply this:

Pay attention to body language, facial expressions, and pauses. If a conversation suddenly quiets down, it may be a cue to shift topics. Look for what’s not being said. If unsure, follow up gently or observe others’ reactions before deciding how to respond.

Morning Greetings and Daily Rituals Matter

Punctuality and rituals like morning greetings are vital in Japanese offices and working environments. Every day begins with a cheerful “おはようございます” (ohayou gozaimasu – good morning) and ends with “おつかれさまでした” (otsukaresama deshita – thank you for your hardword) and “お先に失礼します” (osaki ni shitsurei shimasu – sorry for leaving before you).

Example:

When you leave work, it’s polite to say “Osaki ni shitsurei shimasu” to those still working. They usually reply with “Otsukaresama deshita” (thank you for your hard work).

Why it matters:

These phrases build connection and harmony. They’re more than greetings—they’re gestures of care, appreciation, and inclusion.

The Art of Apology and Humility at Work

Mistakes are handled differently in Japan. Rather than explaining or defending yourself, it’s more valued to take responsibility and apologize sincerely—even if the mistake wasn’t fully your fault.

Example:

If a report is late due to someone else’s delay, you still say “申し訳ありません” (moushiwake arimasen – I deeply apologize). Then solve the problem together.

How to adapt:

Learn the tone of apology and humility. It’s not weakness—it’s emotional intelligence in action.

Meetings: Listening > Speaking

In many Japanese workplaces, meetings are not for open debates or loud brainstorming sessions. They are often used for sharing decisions that were already made behind the scenes or quietly aligning perspectives.

Example:

Jumping in with bold opinions or critiques might feel rude, especially if seniors are present. It’s best to wait, observe, and find the right moment—often in smaller, informal chats.

How to adapt:

Listen first. If you want to offer ideas, do so gently: “One possibility might be…” or “Would it be okay to suggest…” It shows both initiative and humility.

Nomikai – The Unofficial Workplace Bonding

“Nomikai” (飲み会) are drinking parties often held after work. While not mandatory, they’re often where real connections are made—and where the walls of formality gently come down.

Example:

At a nomikai, your boss might become friendly and open up. It’s a chance to bond with coworkers in a relaxed setting. But remember—even here, some politeness remains.

How to enjoy it:

Pour drinks for others (especially seniors) before your own. Never let someone’s glass go empty. And if you’re offered a drink, it’s polite to accept—even just a sip.

Important tip: Even if you don’t drink alcohol, you can still participate. Pour drinks for others, listen actively, and smile. It’s your presence that counts.

The Japanese workplace isn’t just a place of employment—it’s a shared space of harmony, trust, and quiet mutual support. For foreigners, the most powerful thing we can do is approach it with a humble heart, observant eyes, and a deep respect for the group. Even small efforts—like saying “otsukaresama” or staying ten minutes late—can become a bridge to true belonging.

2. Language Nuances: Speaking Beyond Words

Japan is a high-context culture. This means much of communication relies not on words, but on what’s implied. Facial expressions, tone, silence, and social cues carry layers of meaning. As a foreigner, mastering Japanese communication isn’t just about vocabulary—it’s about understanding how and when to speak, or sometimes… not speak at all.

Here are the most important nuances to help you read between the lines and communicate with care and cultural grace.

Keigo (敬語): The Hierarchy of Speech

Keigo, or honorific language, is a cornerstone of Japanese communication. It reflects the speaker’s relationship to the listener, emphasizing respect and social hierarchy.

Example:

Let’s take the sentence:

“Where are you going on long holidays?”

1. Casual (used with close friends or family)

長い休みにどこ行くの?

(Nagai yasumi ni doko iku no?)

- “Where are you going for the long break?”

- Very natural and informal.

- “の?” adds a soft, questioning tone—common in casual conversation.

2. Polite (used in everyday situations like coworkers or acquaintances)

長い休みにどこへ行きますか?

(Nagai yasumi ni doko e ikimasu ka?)

- Polite and respectful, yet not overly formal.

- “へ” (e) and “行きますか” show proper sentence structure.

- Suitable for someone you don’t know very well, but aren’t expected to use honorific language with.

3. Honorific (used when speaking to a boss, client, or someone of higher status)

長い休みにどちらへ行かれますか?

(Nagai yasumi ni dochira e ikaremasu ka?)

- “どちら” is the honorific form of “どこ” (where).

- “行かれますか” is the honorific form of “行きますか”.

- Very respectful and ideal in formal settings or professional environments.

Each level is respectful in its own way—it’s just about adjusting to the relationship and situation.

Application: As a foreigner, using basic polite forms like “arigatou gozaimasu” (thank you) and “sumimasen” (excuse me) can go a long way in showing respect and understanding of cultural norms.

Honne and Tatemae: The Duality of Expression

Honne refers to one’s true feelings, while tatemae denotes the public facade maintained to preserve harmony.

Example: A colleague might agree to a proposal in a meeting (tatemae) but express concerns privately later (honne).

Application: Be mindful that initial agreements may not always reflect true sentiments. Encourage open dialogue in appropriate settings to understand underlying perspectives.

Aizuchi: The Art of Listening

Aizuchi are interjections like “hai,” “sou desu ne,” and “naruhodo,” used to show attentiveness during conversations.

Example: Nodding and saying “hai” while someone speaks indicates active listening and engagement.

Application: Incorporate aizuchi into your conversations to demonstrate respect and attentiveness, fostering smoother interactions.

Indirectness: Saying “No” Without Saying “No”

In Japanese culture, direct refusals can be seen as too harsh or confrontational. Instead, people soften their messages with phrases that hint at disagreement or decline without openly saying it.

Example:

- “That might be a little difficult…” often means “No.”

- “We’ll think about it” may mean “We’re not interested.”

- “We’ll get back to you” might be a polite rejection.

What to do:

Listen carefully to tone and hesitation. Don’t pressure someone for a direct answer. If they say “maybe,” give space—and assume they’re being polite.

Silence is Comfort, Not Awkwardness

Unlike in many other cultures, silence in Japan isn’t uncomfortable—it’s respectful, thoughtful, even warm. People take time to think before they speak. Rushing in to fill a pause can feel overwhelming.

Example:

In group meetings or dinners, long pauses might occur. This isn’t disinterest—it’s reflection.

How to adapt:

Try to be okay with moments of silence. Breathe. Let conversations flow gently. Your quiet presence can be just as appreciated as your words.

Apologies and Gratitude: Everyday Essentials

Japanese communication is filled with expressions of apology (sumimasen, gomen nasai) and gratitude (arigatou, otsukaresama). These are not signs of guilt or weakness—they’re social glue.

Example:

Even when someone did nothing wrong, they may still say “sumimasen” to acknowledge inconvenience. And “otsukaresama desu” (thank you for your hard work) is said daily at work, even just passing in the hallway.

How to use them:

Use “sumimasen” instead of “excuse me” when passing someone or asking for help. End a work call with “otsukaresama desu.” These little words show big heart.

Nonverbal Cues: The Invisible Language

In Japan, people express themselves through subtle gestures:

- A slight nod instead of “yes.”

- A tilt of the head for confusion.

- Covering the mouth when laughing.

- Bowing while speaking on the phone—even if no one can see.

What to watch for:

Be mindful of eye contact (too much can feel aggressive). Avoid grand hand gestures. Use gentle facial expressions. If someone avoids looking directly at you, it’s usually not rudeness—it’s respect.

3. Societal Nuances: Living Gracefully in a Culture of Consideration

Japan is a society built on “meiwaku o kakenai”—the principle of not causing trouble or inconvenience to others. This simple idea shapes everything from how people commute to how they speak, dress, and interact in public. In Japan, society runs like a quiet, graceful dance. It may look effortless, but behind it are centuries of values, customs, and unspoken expectations designed to create harmony. This is not a place where people say what they want, interrupt freely, or act based on personal convenience. Instead, living in Japan means living with others in mind—and this shows up in everything from how you throw your trash to how you stand on an escalator.

Examples:

- Talking loudly on the phone in public transport is frowned upon.

- Leaving trash behind in a public space is considered selfish.

- Showing up late to a group meeting—even by a few minutes—can be viewed as disrespectful.

Why this matters to foreigners:

We may come from cultures that value individuality or casual communication. But in Japan, being aware of how your actions affect others is the foundation of being accepted and respected.

How to apply this:

Before doing something in public, ask yourself, “Will this disturb anyone around me?” If yes—even slightly—adjust. Be soft-spoken, clean up after yourself, and always try to blend in instead of stand out unnecessarily.

Public Silence: The Quiet Power of Respect

In trains, buses, elevators, and even restaurants, silence isn’t awkward—it’s kind. Japanese people are highly conscious of not disturbing others. Loud conversations, phone calls, or even laughter in confined public spaces can be frowned upon.

Example: During morning commutes, entire train cars can be completely silent, even when packed. This silence is a collective courtesy.

How to honor this: Keep phone calls and videos on silent. Speak softly if you must talk. And remember, your quiet presence is a form of respect.

Shoes Off Indoors: Cleanliness Is Deeply Cultural

Removing shoes before entering homes—and even in some restaurants, clinics, schools, and fitting rooms—is about more than just hygiene. It’s about respect for the boundary between the outside world and personal space.

Example: In homes, you’ll usually find a small step or entrance area (genkan) where shoes are removed and replaced with indoor slippers.

What to do: Always watch what others are doing. If slippers are offered, use them. And never wear toilet slippers into other parts of the house!

The Art of Queueing: Order Reflects Respect

Whether it’s waiting for a train, elevator, or even a sale, Japanese people form lines with impressive order and patience. Cutting in line or rushing forward is not just rude—it’s culturally shocking.

Example: At train stations, there are clear markings showing where to stand and wait. Everyone follows them—rain or shine.

Practice this: Stand in line, even if no one tells you to. This is one of the most powerful, silent ways to show that you “get” the unspoken rules of Japanese society.

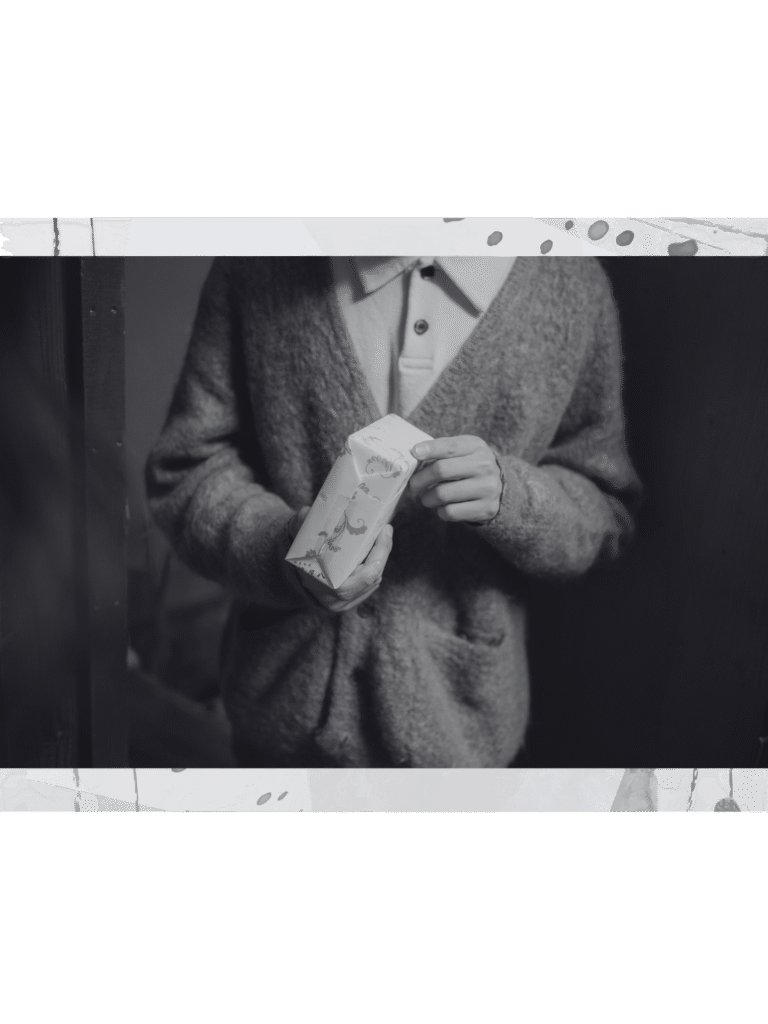

Gift-Giving: Thoughtfulness Wrapped in Ritual

In Japan, gift-giving isn’t about extravagance—it’s about sincerity. Gifts are not just things—they are emotions, respect, and care… wrapped in a box. The thought behind the gift, the way it’s presented, and even the timing all reflect how deeply you care. Whether you’re thanking a colleague, visiting someone’s home, or returning from a trip, there’s always a perfect reason to give—and a perfect way to do it.

And that’s something I came to understand more deeply over the years.

To make my coworkers feel my gratitude for the past year, I wanted to take a little extra step—something simple, but meaningful. It’s not so much, but I wanted to give something they could smile about and remember. So I bought some chocolates—each with a space on the back where you can write a message.

I sat down and wrote my Christmas and New Year wishes by hand, one by one. And wrapped it. Not everyone could read my handwriting well, and some even asked me what I wrote. Others used Google Translate just to understand my note. But that’s what made it special. It wasn’t about the chocolate—it was about sharing a part of me. My words, my heart, and my gratitude were in that little wrapper. And through that small act, I just wanted them to feel happy, appreciated, and seen. You can buy those gift wrapping materials at Daiso, or any 100 yen shop, and the stickers, bought it on Mercari Japan.

This, in many ways, is the soul of Japanese gift-giving. It’s not about what’s expensive or trendy—it’s about being thoughtful. Giving someone your time, your words, your consideration.

How to apply this as a foreigner:

- It’s common to bring souvenirs (omiyage) after a trip to share with coworkers or friends. Even small candies or snacks are deeply appreciated.

- Keep it simple and well-presented. Food, local sweets, or practical items are great choices.

- Presentation matters: wrapping paper, bags, and a polite handoff are part of the experience.

- When giving something personal, like a note or handmade gift, share a bit of your heart—even if it’s not perfect. The effort is what will be remembered.

Why it matters:

In Japan, a thoughtful gift is a silent message: “I was thinking of you.” It can bridge language gaps, strengthen work relationships, and leave a deep emotional impression—often more than words can say.

Giving and receiving gifts in Japan is less about the item and more about the gesture. It reflects appreciation, apology, gratitude, or seasonal greetings.

Helpful tip: Wrap the gift nicely. Present it with both hands and a slight bow. And always say something like, “Tsumaranai mono desu ga…” (It’s nothing special, but I hope you like it.) This humility is part of the beauty.

The Subtle Importance of Greetings and Bows

Greetings in Japan are more than casual hellos—they are rituals of connection and respect.

Basic forms:

- “Ohayou gozaimasu” (おはようございます): Good morning

- “Konnichiwa” (こんにちは): Hello

- “Otsukaresama desu” (お疲れ様です): Used among colleagues to say “Thanks for your hard work”

Bowing:

A slight bow for casual greetings, a deeper bow for respect, and a long, deep bow for apologies or gratitude.

Why this matters:

Skipping greetings or failing to bow may come off as cold or impolite. Even in casual friendships, greetings are key.

How to apply this:

Start every interaction with a greeting and bow slightly, even just from the neck. It shows humility, and it makes a good impression instantly.

Handling Conflict and Criticism: The Japanese Way

In Japan, direct confrontation is usually avoided. People rarely express anger openly. Instead, they use indirect language or facial expressions, hoping you’ll pick up on subtle cues.

Examples:

- A coworker says, “Maybe next time, we can try a different approach,” instead of, “You did it wrong.”

- A neighbor stops greeting you after you’ve violated a noise rule, instead of saying anything.

Why this matters:

Foreigners may miss these cues, leading to misunderstandings. Or we may respond too directly, making others uncomfortable.

How to apply this:

Learn to read between the lines. Observe tone, body language, and small changes in behavior. When unsure, respond with humility: “I’m sorry if I caused any trouble. Please let me know if I need to fix something.”

4. Parenting & School Nuances: Raising Children in a Culture of Harmony and Quiet Strength

Raising children in Japan as a foreign parent is both a beautiful journey and a complex one. You’re not just parenting—you’re learning a whole new philosophy of discipline, humility, community, and quiet encouragement. Japanese society raises children not just for the family, but for the group—teaching them early on to be considerate, resilient, and humble.

As a foreign mom, I’ve found myself both amazed and challenged. I’ve had to shift my own expectations, and in doing so, I’ve discovered insights that I now carry deep in my heart.

Let’s explore some of the parenting and school nuances that can help you navigate—and embrace—this deeply respectful culture.

Group Belonging over Individuality

In Japan, the sense of wa (harmony) is deeply ingrained in child-rearing. Children are taught from a young age not to stand out too much or draw attention to themselves. Group belonging (shuudan ishiki) is often prioritized over personal expression.

Example: At school events, you’ll see children dressed uniformly, moving in sync, cheering not for themselves but for the team. Even birthday celebrations are more modest compared to other countries.

What to do: Support your child while gently helping them understand this group-focused mindset. Encourage cooperation over competition. And if your child stands out naturally, teach them to shine humbly—not to hide, but to respect the group around them.

Gaman: Teaching Patience and Endurance

“Gaman” means to endure, to be patient, to hold back complaints and persevere. Children are quietly taught this from early childhood—whether it’s waiting in line, walking to school in the rain, or staying calm in difficult moments.

Example: During sports day, even young kids cheer for others, if your child cries, comfort them and wipe their tears, and keep going, because gaman is part of building emotional strength.

How to apply this: Praise your child’s quiet efforts. Encourage resilience, not just results. In Japan, patience is a virtue that earns silent respect.

The Role of the Mother (and PTA Expectations)

Mothers, especially, are expected to be deeply involved in their child’s school life through PTA (Parent-Teacher Association) activities, cleaning duties, event coordination, and more. This can feel overwhelming for foreigners unfamiliar with such community-centered parenting.

Example: Some schools rotate classroom helper roles among mothers. Participation is seen as a show of commitment and harmony—not optional, but a quiet expectation.

Tip: If your Japanese is limited, don’t be afraid. Smile, show willingness, and do your best. Most Japanese moms admire sincerity, even more than fluency.

Discipline through Reflection, Not Punishment

Japanese discipline often centers on self-reflection rather than strict punishment. Children are asked to reflect on their actions, write apology letters, or participate in group discussions when mistakes happen.

Example: Sometimes a child who forgets their homework might be gently reminded in front of the class—not with shame, but with an encouragement to be responsible for the group.

How to align with this: Reinforce reflection at home. Instead of scolding, ask your child gently, “Why do you think that happened? What can we do differently next time?” It’s a powerful way to blend your love with the culture’s grace.

Living Etiquette in Japan: The Invisible Rules of Daily Life

In Japan, how you live matters just as much as where you live. Everyday activities like throwing away a tissue, taking a bath, or entering someone’s home are tied to traditions and unwritten rules that protect shared spaces, honor respect, and maintain peace. It’s not just about being clean or polite—it’s about being thoughtful of those who come after you.

Let’s explore the most essential living etiquette every foreigner must know to truly blend into Japanese daily life.

The Art (and Science) of Garbage Disposal

Japan’s garbage disposal system is incredibly detailed and varies by municipality—but one thing is always true: you can’t just throw anything away however you like.

Key categories include:

- Burnable (燃えるゴミ): Food scraps, paper, etc.

- Non-burnable (燃えないゴミ): Metal, plastic items (non-packaging), broken ceramics.

- Recyclables (資源ごみ): PET bottles, cans, glass bottles, cardboard, newspapers.

- Oversized items (粗大ゴミ): Furniture, appliances—require a pickup appointment and payment.

Why this matters:

Garbage days are strictly scheduled, and the neighborhood watches quietly. Improper disposal can lead to public embarrassment, community complaints, or even rejection of your trash by collectors.

How to apply this:

- Read your local town’s garbage guide (usually available in English).

- Rinse recyclables clean.

- Use clear plastic bags when required.

- Attach garbage stickers to oversized items.

- Put trash out only on designated days and times.

Tip: Watch what your neighbors do—and follow suit.

Genkan Etiquette: The Sacred Entryway

The genkan (玄関) is the space at the entrance of a home or some offices/schools. It’s not just a hallway—it’s a transition zone between the outside world and a clean, private space.

What to do:

- Remove your shoes immediately upon entering.

- Step up into the house only with socks or slippers (never barefoot in someone else’s home).

- Place shoes neatly facing outward for easy exit.

Why this matters:

Shoes are seen as dirty and bring the outside into sacred indoor spaces. Ignoring this custom is one of the most obvious signs of being unaware of Japanese manners.

How to apply this:

Always be ready to take off your shoes when visiting someone’s home, a traditional inn (ryokan), or some clinics. Keep your socks clean and presentable—you’ll be showing them a lot!

Bathing Culture: Clean First, Relax Second

The Japanese bath (ofuro) isn’t just for cleaning—it’s a sacred ritual for relaxation, often taken at night. But there’s an order.

Steps in the home:

- Shower and clean your body first outside the tub.

- Then soak in the tub, which is filled with hot water for relaxation.

- The same bathwater is often reused by other family members—so entering clean is crucial.

In public baths (sento or onsen):

- Rinse thoroughly before entering the bath area.

- Don’t bring towels into the water.

- Don’t splash or swim—soaking quietly is the norm.

- Tattoos may not be allowed in some places due to gang associations (yakuza), so check rules first.

Why this matters:

Bathing is a cultural experience that values cleanliness and peace. Breaking the rules—even accidentally—can make others deeply uncomfortable.

How to apply this:

Respect the space, learn the etiquette, and embrace the ofuro as a form of quiet, healing self-care.

Shared Walls, Shared Life: Be Quiet, Be Considerate

Japan’s homes and apartments are often built close together, and walls can be thin. Sound travels. So the lifestyle here includes an unspoken rule: keep your volume down.

Common examples:

- No vacuuming or laundry at night.

- Avoid loud music, TV, or video calls after 9–10 p.m.

- Walk lightly on floors, especially if you live upstairs.

- Close sliding doors gently.

Why this matters:

Japanese culture deeply values consideration for others. Noise pollution is a common reason for friction between neighbors—and few will tell you directly, but you may feel it in strained greetings or avoidance.

How to apply this:

Observe quiet hours. Invest in slippers with soft soles, use headphones for media, and teach your children to be gentle in movement and play.

Laundry Life: Drying Clothes Outside and Seasonal Sensitivity

In most Japanese homes, dryers are rare. Laundry is dried on balconies or by windows.

Cultural notes:

- People are sensitive to weather—sunny days = laundry days.

- Hanging underwear in front is seen as inappropriate; hide it behind larger items or inside.

- During pollen season or yellow sand warnings, many avoid drying outside and use indoor racks.

Why this matters:

It’s part of the rhythm of daily life—and how you handle your laundry can say a lot about your awareness and integration.

How to apply this:

Follow your neighbors’ cues on when and how to dry laundry. Don’t leave clothes out in the rain, and be discreet with personal garments.

Elevator Etiquette: Hierarchy in a Box

Even short moments in shared spaces have structure. In an elevator, the most junior person typically stands near the buttons, while seniors take central positions.

What to do:

- Greet others with a bow or nod.

- Let elders or seniors exit first.

- Avoid talking on the phone or loudly.

Why this matters:

These details, though small, reflect the social mindfulness that defines Japanese daily life.

How to apply this:

If you’re working in Japan, learn the unspoken seating and standing orders, especially in group settings.

Seasonal Transitions: An Unspoken Lifestyle Harmony

Japan’s culture flows beautifully with the seasons. Everything from fashion to greetings, food, and home decor changes with nature.

Examples:

- Hanging koinobori (carp streamers) during Children’s Day.

- Changing curtains or futons by season.

- Offering cold barley tea in summer and hot green tea in winter.

- Using seasonal greetings in letters or emails.

Why this matters:

These customs show respect for time, nature, and social harmony. Being in tune with the seasons is a quiet way to show you understand Japanese rhythm.

How to apply this:

Learn about seasonal foods and greetings. Try using phrases like atsui desu ne (It’s hot, isn’t it?) or suzushii desu ne (So cool today!) to show awareness and connect casually.

Final Thoughts: Navigating Japan with Confidence and Heart

Living, working, or even just visiting Japan can feel like stepping into a world of quiet beauty, deep respect, and unspoken harmony. But if you’re a foreigner, it can also feel like tiptoeing through a maze of invisible lines—nuances, traditions, and unspoken rules that aren’t always easy to see, but are deeply felt by the people around you.

That’s why understanding these Japanese nuances isn’t just helpful—it’s transformational.

When you begin to understand why shoes must be removed at the door, why silence can mean respect, why gifts are wrapped with care, or why children bow before eating—it’s not just about fitting in. It’s about connecting more meaningfully with the people, culture, and spirit of Japan.

These small, often unnoticed details hold the power to unlock deeper trust, create lasting friendships, and help you feel more confident and at peace in your daily interactions.

You begin to carry yourself differently—not with fear of making mistakes, but with grace, respect, and openness. You begin to notice the beauty in the little things: the way coworkers bow slightly as you pass, the quiet gratitude exchanged with a neighbor, the calm order in public places. These are the rhythms of life in Japan—and once you tune into them, everything changes.

Knowing these nuances doesn’t just help you survive in Japan—it helps you belong.

So wherever you are in your journey—whether you’re a traveler planning your first trip, a foreign parent raising children in this unique society, or a long-term resident still finding your place—remember this:

You don’t have to be perfect. You just have to be present, respectful, and willing to learn.

And when you do, Japan doesn’t just open its doors to you. It opens its heart.

Keep learning. Keep observing. And most of all—keep embracing this beautiful journey of cultural understanding with an open mind and an even more open heart.